New snipe, same as the old snipe

70 greater yellowlegs

70 greater yellowlegs71 tree swallow

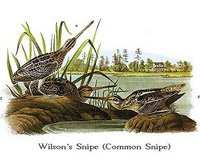

72 Wilson's snipe

MARCH 20, EAGLE BLUFFS, rainy, windy, 40—Officially we were three hours into spring, with snow on the way, when I arrived to look for migrants moving north up the flyway. The tree swallows, gliding and fluttering above the water, were probably thinking they'd jumped the gun. If they actually found insects, they were on the same mission as most other birds there: eat fast and gain calories.

My first shorebird of the year, a greater yellowlegs, constantly on the move across a mudbar, was certainly not a patient feeder. Migration often produces oddities like a lone sandhill crane hanging out with snow geese. A friendly birder had alerted me to the sandhill and Wilson's snipes. But I never saw the sandhill: the snow goose flock, now in the hundreds rather than thousands, was too far away for my scope.

From the Christmas Bird Count and online grapevine, I knew Wilson's snipes had been sighted all winter at Eagle Bluffs. The problem, not fully appreciated by me at the time, was that I had no idea what a Wilson's snipe was. I saw snipes in three places at shallow muddy pools, and they appeared to be common snipes, the only American snipe in my guide.

In theory I prepare for birding with a bit of home study. (Also in theory, I have a home yoga practice—sorry, Linda.) The Sibley guide, the new standard for bird books, is my go-to source, but even that showed only the common snipe. As it turns out, in 2002 it was decided that the so-called common snipe of the Americas was a different species from Eurasia's common snipe, and renamed Wilson's snipe, just what John James Audubon called it.

I understand the splitting, but here's what I don't get. In his description, Audubon writes: "To WILSON is due the merit of having first shewn the difference between this bird and the Common Snipe of Europe." Given that his Birds of America was released five plates at a time over 11 years, Audubon wrote that between 1827 and 1838.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home