March 21, 2006

New snipe, same as the old snipe

70 greater yellowlegs

70 greater yellowlegs71 tree swallow

72 Wilson's snipe

MARCH 20, EAGLE BLUFFS, rainy, windy, 40—Officially we were three hours into spring, with snow on the way, when I arrived to look for migrants moving north up the flyway. The tree swallows, gliding and fluttering above the water, were probably thinking they'd jumped the gun. If they actually found insects, they were on the same mission as most other birds there: eat fast and gain calories.

My first shorebird of the year, a greater yellowlegs, constantly on the move across a mudbar, was certainly not a patient feeder. Migration often produces oddities like a lone sandhill crane hanging out with snow geese. A friendly birder had alerted me to the sandhill and Wilson's snipes. But I never saw the sandhill: the snow goose flock, now in the hundreds rather than thousands, was too far away for my scope.

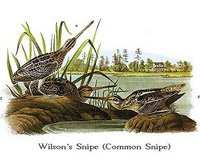

From the Christmas Bird Count and online grapevine, I knew Wilson's snipes had been sighted all winter at Eagle Bluffs. The problem, not fully appreciated by me at the time, was that I had no idea what a Wilson's snipe was. I saw snipes in three places at shallow muddy pools, and they appeared to be common snipes, the only American snipe in my guide.

In theory I prepare for birding with a bit of home study. (Also in theory, I have a home yoga practice—sorry, Linda.) The Sibley guide, the new standard for bird books, is my go-to source, but even that showed only the common snipe. As it turns out, in 2002 it was decided that the so-called common snipe of the Americas was a different species from Eurasia's common snipe, and renamed Wilson's snipe, just what John James Audubon called it.

I understand the splitting, but here's what I don't get. In his description, Audubon writes: "To WILSON is due the merit of having first shewn the difference between this bird and the Common Snipe of Europe." Given that his Birds of America was released five plates at a time over 11 years, Audubon wrote that between 1827 and 1838.

Cherrypicking

69 American woodcock

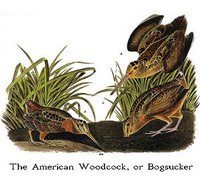

69 American woodcockDuring a two-day display of savvy—or lazy, I'm not sure which—birding, I made quick-hitting visits to three spots in search of a woodcock, winter wren, and sparrows of any kind. Not that I would have ignored an ivory-billed woodpecker cruising past, but my brain was pre-wired for woodcocks, wrens, sparrows. In pickup basketball, when you lag behind at the offensive end hoping for a quick change of possession and easy basket, we called it cherrypicking. This was the birding version—I wasn't even keeping a day list.

At Tucker prairie (complete with re-graffitied field station; now it's the university's turn), I was sure I'd see woodcocks, very high on my list of favorites. By the time I arrived the day's breeze was a small gale, so I headed for a thickety drainage. At thicket's edge I flushed three woodcocks, whose wings whistled as the birds burst from the ground and landed 100 feet away. Though I saw roughly where they landed, I couldn't find them again. Seeing a woodcock on the ground makes spotting a walking stick on a tree seem like finding a cardinal at a feeder.

On the way home I stopped at Little Dixie Lake. The name celebrates southern heritage, as this part of Missouri was known as Little Dixie. Near the lakeshore I searched brush and grasses for sparrows, finding only song sparrows.

Another day I went to winter wren-less Grindstone Creek, hearing a kingfisher and red-bellied woodpecker. In the nearby sparrow-less savanna area were bluebirds and juncos, with the usual pack of 10-20 turkey vultures overhead waiting for unsuspecting hikers to sprain an ankle.

March 11, 2006

Spring promise

65 pied-billed grebe

65 pied-billed grebe66 blue-winged teal

67 greater scaup

68 chipping sparrow

MARCH 11, EAGLE BLUFFS, mostly sunny, 75—Still feeling like Tiger Woods, I returned to Eagle Bluffs for more, more, more new birds. The day was warm and full of approaching springtime, with heavy rain in the afternoon forecast. Henbit carpeted (actually, more like area-rugged) bare fields, and I birded amid a chorus of red-winged blackbirds, snow geese, and chorus frogs.

First and last stops were the long strip of woods along the Missouri River, where I hoped for a pileated woodpecker. In between I found 12 waterfowl species in the pools, including three '06 newbies. I located a nesting bald eagle pair in a tall cottonwood, thanks to an alert from Phil and Pat. The snow geese flock from last week seemed, at a distance, half the size but still a couple of thousand-strong. Besides bird abundance, I saw painted turtles sunning on logs, an otter crossing between pools, and a cat.

March 04, 2006

Snow day

61 wood duck

61 wood duck62 American wigeon

63 bufflehead

64 cackling goose

MARCH 4, EAGLE BLUFFS, cloudy, occasional rain, 40—At least by reputation, birdwatchers offer a mild face to the world, but Big Year birders, from what I've read, can be ruthless in accumulating species. They may love being out among birds and nature, but on the Big Year clock they pursue birds with the raw competitiveness of Tiger Woods going for birdies. Though I didn't wear red (Tiger's tradmark final-round color) or engage in Woods-style fist-pumping, I went to Eagle Bluffs—our local waterfowl and migratory hotspot—for the main purpose of adding species.

Horned larks worked the dry fields, and ducks the pools, not in huge numbers but in variety. I saw a strong lineup of dabblers (green-winged teal, mallard, pintail, shoveler, gadwall, wigeon) and divers (canvasback, redhead, ring-necked duck, bufflehead), plus wood ducks and coots. (Dabblers usually tip forward to feed in shallow water. Their bodies are not streamlined for diving but as a tradeoff they can burst into flight directly from the water. Divers, with large feet and legs set well back, dive proficiently for food but to fly must run across the water surface before takeoff.)

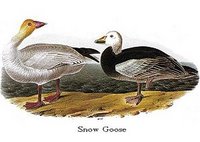

While scoping ducks I heard a low roar from time to time, and finally looked up to see snow geese in the distance. The flock was parked in a partly flooded cornfield, and I settled in about 200 yards away. Out of my ballpark count of 5000, about a third were dark-morph snow geese. At the flock's near edge, 50 white-fronted geese ate and rested. Twice the flock rose loudly and wheeled around the field, settling back down a minute or two later. The few dozen mallards among them didn't budge.

I also found two cackling geese next to the white-fronted. Cackling geese are a new species as of 2004 and were formerly the smaller subspecies of Canada goose. Except for size and slight plumage differences, they are much like the Canada (read about separating cackling from Canada geese here and here). I spent a good hour scanning the flock for Ross's geese, often found with snow geese, but no luck. Snow and Ross's geese now have such enormous populations they are overgrazing arctic breeding areas, with serious consequences for them and other birds that nest there.